by Tara Calaby

In January 1910, a hailstorm caused extensive damage to gardens, crops and buildings in Ballarat’s surrounds. Locals claimed to have seen hailstones as large as hen’s eggs (although the Ballarat Star compared them rather more conservatively to pigeon’s eggs) and the ice could still be seen piled high in places the following day. Over an inch of rain fell in twenty minutes, flooding multiple buildings, chimneys toppled, and hundreds of windows were broken. In Little Bendigo, the Speedwell Hotel was so badly hit that two feet of hailstones needed to be shovelled from the entrance, and at Cardigan, an entire wagon was lifted by the wind, scattering hay in every direction.

The worst of the destruction occurred at the Ballarat Hospital for the Insane, where a 25-acre garden was destroyed and a large number of turkeys and other poultry were killed. Prior to the storm, the garden produced food for the institution’s 700 patients, but its fruit trees were stripped and its vegetables pulverised by the hail, wind and rain. Even the farm buildings were damaged and one whole side of the silo was crushed.

A journalist visiting the site of such devastation watched as the patients who worked the gardens looked with sorrow upon the ruination of their labour.

Mad history makes people uncomfortable. “That must be so difficult,” they say when I tell them my research focus. “All those terrible stories.” They think of chained lunatics in Bethlem Hospital, or of dastardly plots by husbands to imprison inconvenient wives. We’re taught that the history of madness is sensational—the stuff of true crime or horror—but reassuringly distanced from the present, enlightened world. Today, patients are consumers and asylums are repurposed as luxury apartments. Madness is an archaism. We’re no longer mad: we’re neurodiverse. At worst, we’re mentally ill. We’re severed from our forebears and told to be grateful that things have changed.

“That must be so difficult,” they tell me. It’s more like coming home.

Elizabeth Walker was born in Castlemaine in 1857 to parents who had emigrated from West Yorkshire five years earlier. She was the eighth of ten children and the youngest to survive to adulthood. At that time, the Castlemaine district was a bustling goldfield and Castlemaine itself a rapidly growing town where rows of tents greatly outnumbered stone and wooden houses. In England, her father had been a manufacturer, and then a professor of music, but in Victoria, he brushed the dust from his boots alongside labourers and starving miners.

By the mid 1860s, the family was living in Taradale, a settlement large enough for a post office and primary school, located 18 kilometres from Castlemaine. Elizabeth’s only surviving sister was Catherine, the eldest of the Walker children, who was now in her twenties although still unmarried. Eldest daughters were always relied upon to help with housework and to care for their siblings, but Catherine would have taken on more than most, due to the illness of her mother, Martha.

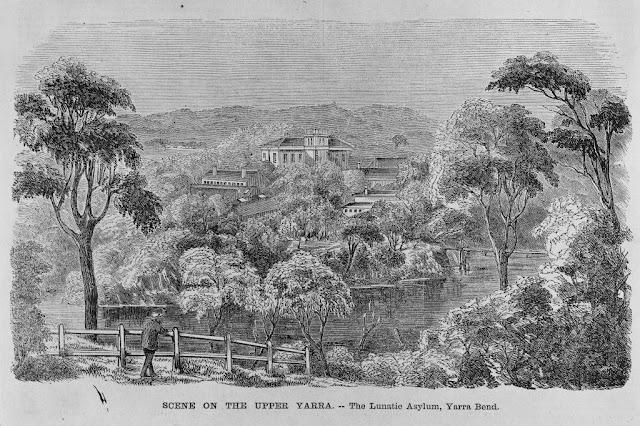

Martha was first brought before the Castlemaine Police Court in 1864, charged with lunacy. She was remanded for medical treatment but returned to her home, only to find herself in court again eighteen months later. In December 1865, she was admitted to Yarra Bend Lunatic Asylum. She would die there in 1890, only months after Catherine was widowed for the second time.

For the last six years of Martha’s life, she was joined in Yarra Bend by Elizabeth.

Biography values the impressive, or at least the fairly-well-known. The shelves of libraries and bookshops are filled with statesmen and celebrities: smug accounts of political treachery and photo-padded gossip about the latest teenage star. Mainstream history is white and able-bodied. Those on the margins are feted only for their trauma. To be given worth, a disabled body must inspire the same people who cringe away from it.

Where in this is there space for the ordinary: for the recognition of those like yourself?

Elizabeth Walker was considered peculiar from the beginning of adulthood. She was fourteen when Catherine married for the first time—old enough to be tasked with acting as housekeeper to her father. By 1880, they had moved to West Melbourne, leaving the yellow dirt of the goldfields for the crowds and carts of the city. Four years later, Elizabeth entered Yarra Bend and was diagnosed with Melancholia. She would remain in the asylum system for the rest of her life.

After fifteen years in Yarra Bend, Elizabeth was transferred to Ballarat Lunatic Asylum, which stood not far from the banks of Lake Wendouree. The doctors there described her as industrious but dull and melancholy, and it was only after she began to look after the ward’s gardens that she grew brighter and more cheerful.

For many years, Elizabeth kept the gardens of the asylum in order. While only men were tasked with working the farm, the care and cultivation of flowers was considered appropriate labour for a woman, and Elizabeth’s interest in gardening was looked upon favourably by her doctors.

To Elizabeth, the asylum gardens offered independence and a sense of ownership that was difficult to find in the institution. At asylums around the world, stashes of items have been found that were hidden under verandas and beneath floorboards by patients who wanted something of their own, kept away from their attendants’ eyes. Elizabeth’s treasures bloomed out in the open, and they stayed with her long after the death of Catherine and the subsequent end of family visits.

In 1910, Elizabeth’s gardens were badly damaged but, under her care, they were soon restored. She lived at the asylum for two more decades alongside her flowers, and then died in 1930 of heart disease at the age of seventy-three.

I have a garden now. I spent Melbourne’s lockdowns in an upstairs flat, connecting with the disabled writing community through a laptop camera, and now I’m surrounded by green. I am better at admiring plants than nurturing them, but already I feel my brain quieten in this new home of hills and trees.

On settlement day, it rained with all the ferocity of an Australian summer. The gutters overflowed and the wind blew sodden debris over the drive and lawn. Afterwards, as always, the colours of the world were brighter.

Was it the same at the Ballarat Hospital for the Insane, I wonder, following the hailstorm of 1910? I picture bruised fruit and battered flowers and exercise yards strewn with ice and leaves. And, in the midst of it all, I see Elizabeth Walker.

Her eyes are just like mine.

* * *

Tara Calaby lives in Gippsland with her wife and too many books. She is a PhD candidate at La Trobe University, researching the social worlds of women in Victorian lunatic asylums. Tara’s writing has appeared in publications such as Strange Horizons, Galaxy’s Edge and Grimdark Magazine and her debut novel is due out in 2023 with Text Publishing.

Next: Failed Escapes – A Dream Diary by David Maney

or