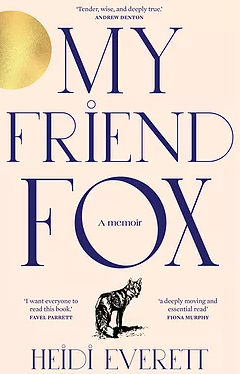

Heidi Everett is an artist, creative workshop facilitator, mental health recovery advocate, social impact facilitator, and projects and events innovator in Melbourne, Australia. ‘My Friend Fox’ is her first book.

Heidi spoke with our Interim Writeability Program Manager, Jess Obersby, about her incredible new debut ‘My Friend Fox’ and all things writing neurodiversity.

I know you’ve been asked this question in many other interviews, but what drew you to write a book?

I love paper! Nah, funnily enough, it was drawing. I’ve been drawn to the art of illustration since I was a kid and drawing a photograph when a camera was unavailable really helped me get through some tricky stuff. Doodling words and symbols is also a form of meditation when your mind is a battle ground. Illustration is a form of writing, only the lines are spatial rather than linear.

In 2011, dog, muse and soul-mate, Tigger, passed away. I was bereft and in shock. I got really unwell and almost died. On the way out of hospital, I thought ‘what can I do to move through this grief?’ So, the over-arching theme of the book started out as a homage to Tigger’s life and story, just getting down the things we’d been through, including the night at the surf club where the fox in ‘My Friend Fox’ appeared. I wanted to tell a story where the hero of recovery isn’t medical intervention, but the love of a dog and being creative.

Why do you feel it’s important to have stories about mental health represented in the Own Voices movement?

Ok, you’ve pressed the Big Red Button. Please skip the next few paragraphs if you like your tea sweet and milky.

A lot of non-fiction about so-called mental health experience is still told from the medical model perspective. Society as a whole, media-makers and researchers still want to know what schizophrenia or depression looks like: here are the symptoms and here’s the recovery.

Unlike most other disability and diverse groups in the 21st century, the blame of mental illness still sits squarely on the shoulders of the unwell person. Acknowledging the environmental causes of distress, as other disabled groups do, takes away the illness and shines a big bright light on the injury. So, without our voices disrupting the medical humdrum, mental illness will remain an illness in the mental health system.

Using my inner voice to speak my outer story means I’m moving in a way that’s accessible. Through the natural language systems of the arts and culture, we are enabled to process the thorns and roses of living on the streets, being alone, and more shared norms like family yearning, poverty, heartbreak, grief, even moments of joy like finding on love, luck and friendships. My story becomes ours, not my counsellor’s.

My book is about revealing the ills of the psychiatric system, as much as it is my survival. I want to show that if I did any overcoming, it was of the mental health system that put me down. My triumph isn’t that I recovered from mental illness, it’s that I’m healing from all the things that put me there.

You have a very broad arts background. I understand ‘My Friend Fox’ was prompted by a collection of songs, poems, drawings and essays. What was the process like, making all these different creative media come together into book form?

The first inspiration for ‘My Friend Fox’ was actually a beaten-up folder of original songs I was carrying around to community gigs in Melbourne for years. All my songs are little anecdotes of the psych ward, sad times, living the streets or the love of my dog and happy times. It wasn’t hard to decide to write one long-form song connecting all the verses. The book isn’t a literal rendition of song lyrics, but the themes, metaphor, rhythm and tempo are all there. I also do lots of talking between my songs at gigs — it’s like being out the back surfing waiting for the waves or pottering around the bush while looking for something really interesting. You need to keep the connection.

My illustrations in the book are what I call ‘photographs’ of the scenes that I experienced in hypersensory situations. The images from these moments stuck hard in my mind’s eye, so deciding which sections would be illustrated was fairly easy for this reason. Drawing the images onto paper was like finally processing the film and printing the photos out. These images are providence of my experience and, like war art and courtroom portraits, the psych system can’t claim innocence, even if the CCTV footage and file notes have seemingly been erased.

Lyndel Caffrey, my Writeability mentor, was a crucial part of making sense of my book when I had folders of disconnected essays. Lyndel really got inside my words and pages, pushing me to think about my story beyond my own small line of sight. I learned so much about my narratives from Lyndel, and really upped my progression from songwriter to author. Jax, my Publishability mentor, organised for my manuscript to undergo a structural edit because after fifty thousand re-writes, my book had turned into a big bowl of spaghetti. This structural edit really sorted things out for me and gave the final ‘oomph’ to complete the manuscript for my publisher. Just when I thought everything was done and dusted, my publisher asked me to work through their edits which gave the book one last rinse and vacuum.

This is obviously a deeply personal story for you, as all memoirs are. How did you protect yourself and make sure you were practising good self-care while you were writing it?

I’ve told the stories in this book so many times to doctors, case-workers, counsellors, researchers and psychiatrists. This is the first time I feel I’m looking after them and myself properly. I’ve also told my stories hundreds of times through my songs, public speaking and advocacy work. I’ve done my apprenticeship. I’m good.

On your webpage you describe yourself as ‘producer, artist, writer, mental health arts advocate, and social impact innovator’. I find that last term really interesting. Can you explain what it means?

Without making myself sound super poxy, I usurped the term ‘social impact’ from a few conferences I’ve sneaked into. I believe it means doing work that improves society for people of diverse backgrounds, bodies and minds.

But I’m not satisfied doing what everyone else is doing because that’s my neurodiverse kryptonite, so I come up with fun new ways to make society more accessible and embracing of people’s hearts and minds. I have the freedom of not being an academic! I feel sorry for my peers who are trapped by their non-disabled employer’s idioms. My little NFP arts organisation Schizy Inc and my other arts projects like Qualia Theatre get to play. Instead of celebrating Schizophrenia Day with a lecture about schizophrenia, we started an industry-level film festival where the films are only made by filmmakers with schizophrenia. This is subversive because most films about schizophrenia are about people with ‘schizophrenia, the illness’ (cue spooky violins and crooked camera angles). Qualia Theatre raises human rights issues not yet considered in mainstream mental health advocacy, things like Auslan interpreters in psych wards and wheelchair accessible common areas. Deaf people get admitted to public psych wards and there are no interpreters. Mic drop.

I also like having fun. That’s illegal in the mental health system.

Since COVID-19 lockdowns, many isolated people want their lives to ‘get back to normal’, even to the point of protesting, and the government is talking about living with a new ‘COVID-normal’. Unfortunately for disabled and mentally ill people, this sort of isolation often is normal. If people can learn from this, what do you hope might change?

Oh, you found the Other Big Red Button. Irony alert!

Apparently for me to be normal, I have to go out and make ten friends and family in the next week, even though I haven’t managed to wrangle up a singles social bubble for the last two years. Then I can invite them into my home (the one where there’s no heating or hot water because I can’t afford it and ignore my aversion to having anyone in my home because it completely skews my brain). I also need to want to go to the pub and a restaurant, and be able to afford it. I need to let go of being terrified at the thought of more than two people talking at once, over music, children and the sound of plates and cutlery, delivered with a cacophony of smells, harsh lights and movement.

My lifelong paranoia about government controlling my thoughts and whereabouts is now brushed off as ‘anti-’, meaning I will now need to suddenly be OK about using a smart phone with wi-fi and linking my personal identity to a centralised agency, even though I’ve been attending counselling and prescribed anti-psychotics to manage this very fear for the last thirty years, a fear which has nothing to do with the people who have suddenly become overly concerned with government-mandated rules.

My little Nokia will need to be replaced with an iPhone 13 and I will spontaneously be able to process the information and technology to use the apps contained on a virtual screen that my mind cannot perceive. My social anxiety spiking even thinking about going out the front door to the letterbox and running into a neighbour will need to be put on hold as I welcome in this new age of social confidence.

Seriously, for society to be neurodiverse-normal (is there such a thing?), we’d have elders and disabled leaders on TV and radio consistently talking about these realities, rebuilding small and local level arts and culture, finding ways to be compassionate to those we don’t agree with, and placing far less media emphasis on major arts groups getting back to entertaining people getting pissed in a pub after watching overachieving men playing sport.

End irony.

Are you currently working on any creative projects? Can you tell us about them?

I have two plays in suspended animation and a new short film with Qualia Theatre that is busting to be screened featuring three diverse artists speaking in their own voices about human rights issues in psych wards. ‘Fyre’ is the theatrical version of My Friend Fox. Hopefully we can get to rehearse these plays and show the film ASAP.

At Schizy Inc, we’re planning Mojo Festival 2022 which is a six-month program of arts-making and a culmination event on World Schizophrenia Day in May. There are a bunch of other arts and advocacy projects to fire up as soon as neurodiverse end of lockdown happens.

I’m also doing community arts workshops and lived experience projects which will be on my website as they rock up.

We’ll be giving away copies of ‘My Friend Fox’ to the lucky winners of our weekly Subscriberthon book packs. To enter the running for a weekly book pack and other exciting prizes this Subscriberthon October, remember to join as a member or renew your pre-existing membership before the end of the month!

To find our more about our Writeability program and sign up to the Writeability news, visit: writersvictoria.org.au/writeability