Declan Fry is a writer and essayist. Born on Wongatha Country in Kalgoorlie, he has been awarded a Peter Blazey Fellowship and the Lord Mayor’s Creative Writing Award, shortlisted for the Judith Wright Poetry Prize, and nominated for the Pascall Prize for Arts Criticism.

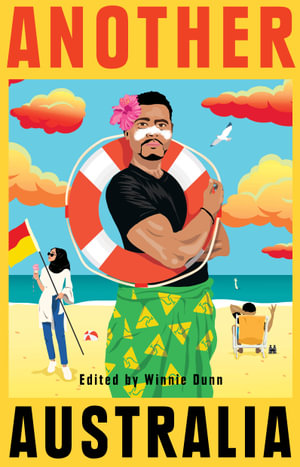

Following the publication of Another Australia, Writers Victoria Membership Officer Lou Garcia-Dolnik spoke with Declan about his contribution to the anthology, a genre-defiant piece of experimental fiction, organic repetition, the travails of intimacy, and organic repetition.

Can you tell us what ‘Nothing Remembered and Everything That Was’ is about? What were some of the inspirations behind the story?

‘Nothing Remembered and Everything That Was’ is about a person traveling in the Netherlands who meets a woman named Aline. Aline lives in Alkmaar, 40 kilometers or so north of Amsterdam. Both of them have to confront insoluble aspects of their relationship, and of their pasts.

The story emerged while I was reflecting on Bjork’s song ‘Hyperballad’, and a cover of that song by the Marcin Waselewski Trio, whose album, like so many released on the ECM record label, features a moody, suggestive, aggressively wintry image. There was also the opening lines of Yasunari Kawabata’s 雪国, Snow Country, with its invocation of the snow, its ambiguity and indecipherability.

For a time I toyed with the idea of naming the story ‘Hyperballad’. That didn’t happen, although I did curate a playlist of songs that speak to the story’s themes and its rhythms.

What I thought was particularly beautiful in NOTHING REMEMBERED is that even sentences take the form of journeys, digression and aside becoming a logic unto themselves. I wonder if this disposition is one that migrated from your critic’s (or perhaps even your poet’s) mind? Or do you see fiction as a genre with its own set of intentionalities, ambitions?

Certainly it relates to criticism insofar as, when we look at the Anglophone tradition of attempting to secure a firm, impermeable boundary between the realms of fiction and nonfiction – or between the imaginative and discursive – it’s hard not to sense the whole endeavour creaking beneath the burden of territorial vigilance. I certainly hope to see more work that ignores the separation between the two.

For example: many writers are afraid of employing repetition in their prose. I’ll say it again: many writers are afraid of employing repetition in their prose. They think it will make them look slovenly, lazy. In fact, fidelity to repetition can function as fidelity to the rhythms of thought, the ways in which we experience patterns of thinking in our own lives.

As for the question of the sentence as a journey: yes. I think the period has become a bit of a stumbling block. It. Stumbles. Many languages, in their earliest written forms, eschewed punctuation. Punctuation may channel a sentence down a certain pathway, yet its absence can open up new possibilities. Personally, I value digression and asides, because I think that part of the written word’s pleasure lies in the opportunity it offers for such digression, for containing multiple objects of attention, reminiscence, reflection, each of them competing and interacting with one another. Like repetition, the journeying sentence, I believe, may perhaps hew closer to some aspects of thought as we experience them.

In a sense, this is one of the differences between – to take just one example of genre demarcations – memoir, say, and fiction: fiction may intensify the apparent falseness of reality, but it is a falseness which is, often, its primary material evidence of constituting reality. The two share a certain kinship, at least in their narrative qualities, and despite being based on differing materials and techniques.

I couldn’t help but return to the narrator’s assertion that ‘movement made everything familiar’ as a kind of guiding principle for the work. NOTHING REMEMBERED vitalises and revitalises that axiom, showingat once the awkwardness of relationality in transit and the difficulty of remaining static in places that aren’t one’s own. Was this fixation with movement and transience something that arose organically in response to reimagining ‘Australia’, a place which (very intriguingly) only features as an ’elsewhere’ in the story?

I think that’s a good way of putting it. “The awkwardness of relationality in transit and the difficulty of remaining static in places that aren’t one’s own”: I like that idea. Transience, I think, lies at the heart of life and writing. There isn’t enough time. Everything goes. Being elsewhere, finding yourself in a state of longing, desiring: these are the things that remind us of how quickly all that we know can vanish, that it is vanishing even as we come to appreciate it. Certainly in Australia – at least in our more urban, commercial spheres – society works very hard to distract you from transience, from the existential question of who you are or who you want to be. I’m often reminded of the California depicted in Aldous Huxley’s After Many A Summer: all pleasure and no pain, bread and circuses but no engagement, no surprise or wonder. Our lives are fantastically small and short, but we rush to make them large. Then again, sometimes there is almost too much fullness in being.

For both of the characters in ‘Nothing Remembered’, it’s their engagement with one another, with the places they’ve travelled from, or to, or within, that impresses itself most urgently upon them, testing the fracture points in their lives, all of the little failures. When we come up against a challenge – something that oppresses us – we sense the demarcations and limits of our existence.

In this sense, ‘Nothing Remembered and Everything That Was’ is primarily about intimacy – and the human risk of intimacy. Whether in belonging or relationships, there’s always a danger to pursuing passion and desire. There may be recognitions. There may be misrecognitions. The narrator is someone acquainted with this paradox, being both recognised and misrecognised. They also find themselves doing the same. Australia is an elsewhere for the narrator, I think, because Australia has made him into an elsewhere. They are someone who – as they say – is Australian, but only in a conditional sense. Thus both he and Aline, the Dutch woman he meets, are forced to practice a labour of love which Baldwin, so sharply and tenderly, described as knowing: the desire both to know and to be known. It’s an act which requires vulnerability, a vulnerability which is also, paradoxically, a variety of power.

What are you hoping readers take away from the story?

I hope readers take from my story whatever they wish to. Many people say they ‘don’t have time to read’. We have to make time. Speaking purely for myself, as a reader, what I really enjoy is when writing – writing that transports you – takes the time you didn’t think you had to read and extinguishes it.

Equally, I have to admit, I hope that readers enjoy the writing, the language. Perhaps the affirmation of desire and energy in the prose. The resonance of words on the page is fundamental. Some books come equipped with prose so bad it makes you regret having begun to read them at all.

I hope, perhaps, that they might be transported. It’s what I love, as a reader. To be – in every sense – carried away.

If you could have dinner with an ‘Australian’ writer, alive or since passed, who would you choose and why? I’m especially interested to hear what dish/es you might pair with this writer and where you might choose to take them!

Gary Crew. Biangbiang noodles on Swanston Street, then Lavezzi on Lygon for gelato.

Crew provided something of an early literary education for me. Growing up in Kalgoorlie, his work showed me what, I believe, in retrospect, was a formative universe of fantastic and uncanny literature. Some of it, like Robert Louis Stevenson, I had come across before. In fact, he was the very first author I remember making an impression on me. My mother read to me from a pocket-sized copy of Treasure Island that she had bought at the local mall. I was deeply haunted by the chapter about the “black spot”, with its accompanying illustration of a sailor afflicted by the malady. My father introduced me to Don Quixote and H.G. Wells. It was the sort of motley, omnivorous reading many of us experience early in our reading journeys.

Through Crew, and especially through an anthology he published, Crew’s 13, which was illustrated by Shaun Tan, I began discovering work that has stayed with me for life: Guy de Maupassant. Théophile Gautier. Jan Potocki. Prosper Mérimée. Mary Shelley. Gérard de Nerval. Hume Nisbet – who actually sets a gothic narrative in Western Australia. There is a line in his work, ‘The Haunted Station’, which, when I read it recently, sounded strangely similar to certain aspects of the rhythm in ‘Nothing Remembered’:

Behind the house, or rather from the centre of it, as I afterwards found out, projected a gigantic and lifeless gum tree, which spread its fantastic limbs and branches wildly over the roof, and behind that again a mass of chaotic and planted greenery, all softened and generalised in the thin silvery mist which emanated from the pool and hovered over the ground.

And, of course: there was Poe. There has always been Poe. Poe represented, for me, everything that made art and literature worthwhile. Its ability to transmogrify. To test the limits of existence. And to encourage you, as I felt encouraged, to feel like existing at all.

Courtesy of Affirm Press, we have three copies of the relentlessly exciting Another Australia to giveaway to three lucky members. To enter the draw, email your postal address to [email protected] by Sunday 25 September with ‘Another Australia’ as the subject.