Your much-loved and award-winning novel ‘The Bone Sparrow’ was about a child in a refugee camp. ‘No Stars To Wish On’ was based on institutionalised children of Australia’s Forgotten Generations. ‘The Ones That Disappeared’ is about three trafficked children searching for freedom and hope. When you get an idea for a book, what come first – the issue or the characters?

I think for me, the story comes first. It is always a situation, or a question that gets me excited and starts my brain racing. With Bone Sparrow for example, it was wondering what life would be like if the only world you knew existed was the world inside the barbed wire fences of a detention centre. Very often the story is wrapped up in an issue, and pretty quickly I have a fairly good idea of who my characters are – I just need to wait until their voices speak clearly to me. But it is definitely the story that starts me off and keeps me going. I am always a little horrified if someone refers to my writing as ‘issues’ based – because in my mind the books are really about the characters, who just happen to be living in a time or place that requires a struggle to survive. (That could be where the issues element comes in…hmmm…). I guess we all struggle at different points in our lives, and it is finding the strength to push through which is the challenge. I put my characters in some of the most difficult situations, partly because I want to find out how someone could find strength and hope and even some moments of happiness in those situations.

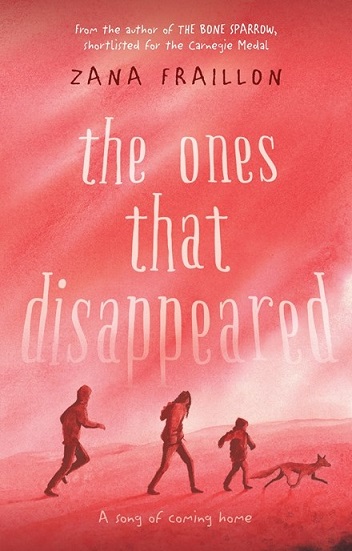

‘The Ones That Disappeared’ is a haunting and evocative title. What inspired the title and how does it relate to the narrative?

Originally I had titled the book Armadillo Tears (there was an armadillo in it… he was slowly and sadly edited out, but I have faith he will return in a later book…). So for a while, I was a little stuck for a title. At the same time, I had received feedback from my publishers about Esra’s voice. They felt her voice wasn’t coming through strongly enough. My publisher in the UK spoke to me about how from a psychological perspective it felt very real, that a person who had been through such trauma would be unforthcoming and removed, but stressed that the reader needed to get inside the character’s head more. So I had a long talk with Esra – we walked along the river and I did my best to convince her to open up some more – and when I got home I wrote Esra’s poem. It came to me very quickly and easily and felt very true, and very important to her. So important that I felt it needed to be included in its entirety in the book, which is why it makes its appearance after the story has finished. One of my publishers pulled a line from the poem “We are the ones that disappeared” and suggested that as the title. We knew pretty quickly that this was the way we wanted to go. It felt right on so many levels, and spoke directly to the issue – that these children do simply disappear. We have no idea where they are, where they will end up, what they will be forced to do, or even if they are alive. They are simply gone.

‘The Ones That Disappeared’ focuses on three enslaved children. The pages are infused with magic-realism and a child’s delight in imagination. Was it difficult to strike a balance between that sense of a child’s hopefulness and sense of play and the darker, more brutish elements in the book?

I didn’t find that balance difficult at all. I love magical realism, I love imagining that there is a whole other layer to the world if only we know where to look. When we read books, we are already suspending belief in the world we know for a short time, and I love pushing those boundaries just a little further. I do however, always want to make it possible that there was no magic happening at all. Perhaps Riverman was just a homeless man who stole the jacket and happened to have a wooden leg? Perhaps it is simply a series of coincidences?

One of the things that continues to strike me whenever I research children living in such dire and horrific circumstances, is the way in which so many of them are still able to find happiness and joy in simple childhood things. So often, children don’t realise how much they are going through. They don’t necessarily see the horror as we see it. For children, this is just how they are growing up. They are so quick to smile and laugh, despite everything they have been through, and everything they will have to go through in the future. It is that sense of hope and resilience which is so strong in children that I wanted to convey.

Your three novels are marketed for older children and young adults but they are also enjoyed by adult readers. Do you write for children or for adults, or both?

I write for children, however, I really, really hope that adults will read my books as well. I love reading books written for children and young adults, and I feel that so many adults are missing out on some amazing literature because they discount children’s books as inferior. I write my books for children, because, at least at the moment, my books are about discovering who you are, about injustice and standing up for change. Children and young adults are the ones most open to connecting with these ideas. We adults forget far too quickly. We get on with our lives and put things out of our heads. But children and young adults are imagining a very different future. They are imagining their role in the world. They are imagining how the world will change. They are thirsty for knowledge about what is happening all over the world – not just in their own social circles, but in the dark corners, in the hidden spaces, in the places that we aren’t shown or that we don’t talk about. It is this that excites me at the moment. That idea of revealing parts of ourselves, our history or our world that we are unaware of. So I write for children, but I write books that I hope everyone can read and connect with.

You’ve also published picture books and a series for middle-grade readers. Does being a trained school teacher help you write for these different age ranges? Do you have a favourite age to write for?

I think spending a lot of time with kids helps me write for different age ranges. I really enjoy the company of kids, the way they see the world is so interesting and full of insight and often completely original and surprising. Anything is possible for kids, and I love that. I particularly like writing books that have characters who are transitioning from childhood to adulthood. I remember that moment in my life so fiercely, and it is a time I keep returning to in my writing. It is a time when we start to see ourselves as individuals, when we start to question the world and those who have power in our lives. We begin to see that what we thought we knew isn’t always true, and we need to come to terms with that and work out where we want to stand, what sort of people we are. It is such a wonderful, exhilarating, frightening and enormous time in our lives, and is full of such great writing moments.

Having said that, I adore writing picture books as well. I love the way language is used, and I really enjoy collaborating with an artist to construct meaning. I am working on three new picture books at the moment, and they allow me to do different things with my writing, to be more poetic, and to play with language and meaning more. But just as adults should be reading children’s books and YA, I strongly believe that older children – and indeed adults – should continue to read picture books as well.

If all the chocolate in the world disappeared, would you still be able to write?

Imnjhr njhse jklujf ma, huiyiua njkhyiuh wedhgsdf ejuyg mni;dsurq a ih fdih akjhnoi…

What is the best piece of advice you received when you were an emerging writer?

To write what you want to write. Ignore audience. Ignore trends. Ignore teachers and friends. Write as though no one will ever read it. Write purely for yourself. It is really hard to do, but for me at least, it is the only way I can write honestly. If I am focussed on my audience, or on trying to write an award winning masterpiece, it is impossible to listen to the story and the characters. Just write. A lot of it will be rubbish. But then there will be the small jewels. Take those and put the rest in an ‘extracts file’. Keep going, keep mining for jewels, keep ignoring all those other critical voices. If no one is going to read it anyway, what does it matter what you write? And at the end, when you have got as much as you can from the story, then you can decide whether to send it out into the world or not.

Zana FraillonZana Fraillon was born in Melbourne, but spent her early childhood in San Francisco. Zana has written two picture books for young children, a series for middle readers, and a novel for older readers based on research and accounts of survivors of the Forgotten Generation. She spent a year in China teaching English and now lives in Melbourne with her three sons, husband and two dogs. When Zana isn’t reading or writing, she likes to explore the museums and hidden passageways scattered across Melbourne. They provide the same excitement as that moment before opening a new book – preparing to step into the unknown where a whole world of possibilities awaits.

‘The Ones That Disappeared’ is published by Hachette |

|