Sarah Walker is a Djilang/Geelong-based writer, artist and photographer. Her writing is primarily creative nonfiction, considering issues of anxiety, control and intimacy. She was runner-up in the 2019 Calibre Essay Prize and received the 2020 ABR Victorian Rising Star award. She was shortlisted for the 2022 Commonwealth Short Story Prize; a finalist in the 2020 Walkley awards and the 2020 Nillumbik Prize for Contemporary Writing; a semifinalist in the 2020 Disquiet Literary Contest and runner-up in the 2017 Darebin Mayor’s Writing Award. She has been published in Meanjin, Kill Your Darlings, Overland and The Guardian, reviews arts for the Australian Book Review and co-hosted the podcast Contact Mic. Her first book, The First Time I Thought I Was Dying, a collection of non-fiction essays about the unruly body in late capitalism, won the 2021 Quentin Bryce Award.

Following her shortlisting in the Commonwealth Short Story Prize, our Writeability Program Manager, Jess Obersby, spoke with Sarah about her writing process, researching apocalypse preppers and putting your (polished) work out there.

Congratulations on being shortlisted for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize. What made you submit to this prize in particular?

Thanks very much! Look, one answer is: because prize money is great, and being shortlisted is helpful for visibility. Another answer, also true, is: most of my literature networks, as both a writer and a reader, are pretty localised to Australia, NZ, the US and the UK. The amazing thing about the Commonwealth Prize is that it connects a huge network of people globally who all share this complicated experience of having been colonised. This means that I am in a complicated cohort of writers with extraordinarily different life experiences, all cohering those experiences into short fiction. To be part of something that embraces humanity on such a large scale feels quite moving, as we all figure out what it means to be Commonwealth citizens today. We share some quality of our pasts, and it’s fascinating to be considering, en masse, how those qualities impact our present and future.

Tell us about ‘Slake’. What was the inspiration for the story?

For some years, I’ve been obsessed with apocalypse preppers. It was fascinating watching that community respond to the early weeks of the pandemic, because there was a real feeling that for many of them, it looked like this was the big moment they’d been literally preparing for. Being in those online spaces held a kind of dark electricity. There were countdown clocks and graphs and spreadsheets containing signs of societal collapse to look out for. Some of those people were totally ready to climb into their bunkers and start defending the perimeters of their land with assault rifles.

And then, of course, what the pandemic actually required of most of us wasn’t every-man-for-himself reactive individualism; it was a form of collective care. I can imagine how confusing that must have been for diehard preppers, who were telling each other that war was coming, and hearing instead, ‘What you really need to do is stop panic buying, start wearing a mask, and start looking out for your community.’ That group responsiveness is quite anathema to a lot of prepper thinking.

Many people in prepper communities, though, do stress that while having tinned beans and first aid kits are helpful, that there are other essential skills for disaster which are much softer and kinder: building caring relationships with neighbours, learning how to grow food, developing strong social bonds.

‘Slake’ tinkers with these conflicting impulses in the wake of catastrophe. Set in the aftermath of apocalypse, where preppers and gardeners come together to try to survive, the story considers the tensions between individualism and community in the wake of large-scale disaster, and how we find resilience when things keep going wrong.

Can you tell us about your writing process?

I know a lot of writers find that discipline and consistency are essential for their work. I know people who get up at 6 am, write for hours and then end the day with 300 perfectly polished words.

I am not that kind of writer. Never have been. Most of my writing gets done in big month-long bursts of energy, interspersed with long periods of fallow time. When I’m writing, I have a minimum of 1000 words per day, which usually takes me about 45 minutes to write. Editing is slower, and much more considered. I’m a big believer in churning out words as quickly as possible, and then sorting and refining them later. Maybe that’s why I enjoy editing my own work: I like writing so quickly that I don’t have time to question what’s there, then returning slowly, like a geologist, unearthing the structure that holds the sections together. I’ll regularly cut half of what I’ve written, but I’m always pleased to find that there is good content amongst the chaos. After the first big edit, I go back and fill in gaps, massage the pieces so they fit together. This dance, between generative and destructive modes of working, tends to mean that I find threads in the writing that I didn’t expect; ideas that were tacit in my thinking, and that I can return to and amplify. It makes the finished work much richer.

I don’t write at a particular time of day, or in a particular place. I’m always happier when I get the words done early in the morning, but most nights see me frantically tapping away at 11 pm. Order doesn’t suit me very well. I think the chaos keeps the writing alive. Or at least, that’s what I’m telling myself.

Do you have any tips for writers looking to submit to competitions, especially emerging writers who are just finding their feet?

I am a huge advocate for submitting (tight, finessed, ruthlessly edited) work to prizes. Recognition in the form of being shortlisted or placing is great. It attracts publishers and agents. But some of the best opportunities in my career have come from prizes where my work wasn’t shortlisted at all, but one of the judges rad it, was interested in it, and passed it on to someone else. You never know who’s reading.

The great thing about prizes, too, is that they impose a form, a word count and a deadline, which are the three essential mechanisms for finishing work. It was the Horne Prize that made me finally sit down and wrangle some very fluffy writing into something tight and considered. The resulting essay, Floundering, wasn’t recognized in the competition, but it got the attention of my publisher. I wouldn’t have ended up with a book deal without it.

You work across several art forms. How does your art and photography intersect with your writing?

They bleed into each other a lot. One of my first hints that I was a writer was that I kept feeling the urge to annotate my photos, to incorporate text into them. My fine art work is about using comedy and speculative narrative to talk about death and dying. Those tactics are literary ones, and so my work tends to involve text either directly on paper; or in the form of scripts for audio and video; or as ideas around communication that inform more abstracted work. They’re all linked by an interest in language and the ways that narratives sustain us, reassure us, and help us make sense of the unknown. One of the fundamental threads in all my work is the fear of losing control. It drifts across my essays, fiction, sound walks and video works. It’s a very sustaining obsession that emerges in many forms!

Can you tell us about what you’re working on currently?

Sure! I’ve recently finished a book manuscript called The Part Where We Panic, which is a collection of apocalyptic metafiction (by which I mean: short stories about disaster, tied together with interstitial text wondering why we’re so obsessed with the end of the world. A collection that starts critiquing its own premise).

This month is another 1000-words-a-day month. I’m working on a novel about an elderly woman, Pam, and her ten-year-old neighbour, Charlotte, as the world around them begins to cave in. Cheery. Haha. I’m interested in writing a kind of anti-apocalypse road trip story. Often, in the media we’re used to, shit hits the fan, at which point the protagonists have to go on a quest to find a place that’s better and safer. What happens if your protagonist is elderly, if they can’t move easily, if they’re unwilling to leave the place they understand? What does a shelter in place narrative look like? It’s grim and funny and strange. I’m enjoying working on it.

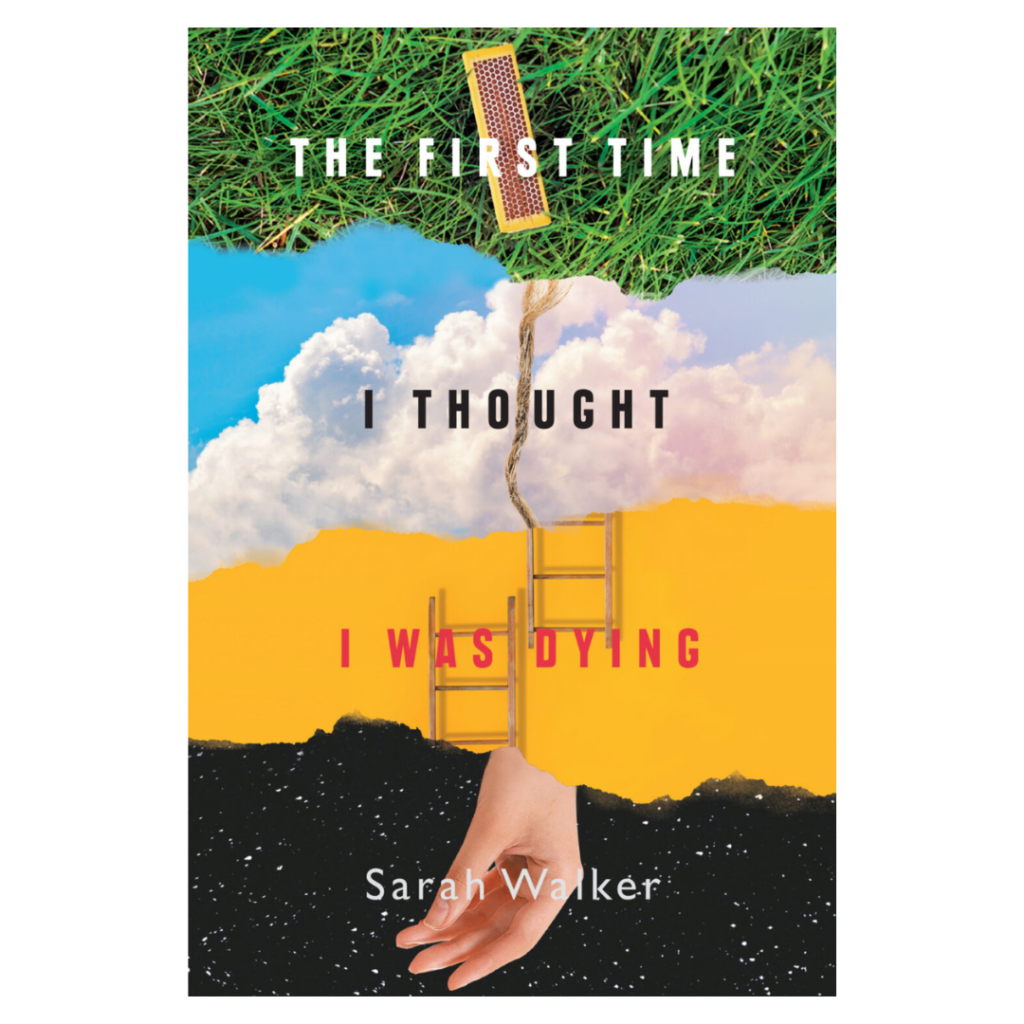

Courtesy of UQP, we have three copies of Sarah’s stunning collection of essays, The First Time I Thought I Was Dying, to giveaway to three lucky Writers Victoria members! To enter the draw, email your postal address to [email protected] by Sunday 21 August with ‘The First Time I Thought I Was Dying’ as the subject.